Review: The Role of Human Papillomavirus in Virus-Induced Carcinogenesis

Abstract

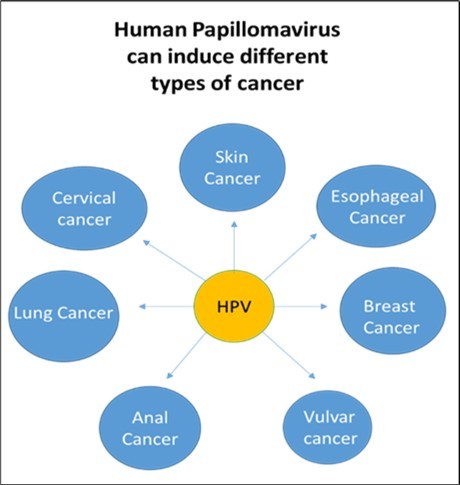

Viral infections contribute to a significant proportion of human cancers, with human papillomavirus (HPV) being one of the most well-established oncogenic viruses. This review summarizes HPV biology, transmission, classification, molecular mechanisms of carcinogenesis, epidemiology of HPV-associated cancers, and current and emerging preventive and therapeutic approaches. particularly HPV-16 and HPV-18, drives malignant transformation through the E6 and E7 oncoproteins, which disrupt tumor suppressor pathways p53 and Rb. Prophylactic vaccination programs have demonstrated remarkable success in reducing HPV-related disease burden, but disparities in coverage remain. Cutting-edge strategies such as CRISPR/Cas9 and RNA-based therapeutics offer promising avenues for treating established infections. Integrating these biomedical advances with robust public health initiatives is essential to ultimately eliminate HPV-associated cancers worldwide (Figure1).

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: Anubha Bajaj, Consultant Histopathologist, A.B. Diagnostics, Delhi, India.

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2025 Zahraa M Essam, et al.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Introduction

Cancer remains a major global health challenge, imposing a significant burden on individuals, families, and healthcare systems 1. Understanding the mechanisms underlying cancer development is crucial for advancing prevention and treatment strategies. Among the various factors contributing to carcinogenesis, viruses play a significant role, with an estimated 15% to 20% of human cancers linked to viral infections 2. Oncogenic viruses contribute to different stages of cancer progression, with their association with specific cancers ranging from 15% to 100% 2.

The link between viruses and cancer was first proposed in the early 20th century when Ellermann and Bang demonstrated that cell-free tumor extracts could transmit avian leukemias, followed by Rous’s identification of a viral origin for sarcomas in 1911 3, 4, 5. Since the discovery of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) as the first human tumor virus in the 1960s, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has classified several viruses as type 1 carcinogens, including EBV, Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), high-risk human papillomaviruses (HPV), Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) 6. Viral infections are estimated to contribute to approximately 15% of all cancer cases worldwide, with this percentage being higher in developing countries 7.

Among oncogenic viruses, human papillomaviruses (HPVs) are one of the most well-established contributors to cancer. HPVs belong to the Papillomaviridae family and are non-enveloped viruses with a double-stranded DNA genome of approximately 8,000 base pairs. Based on their oncogenic potential, HPVs are classified into low-risk and high-risk types 8. Low-risk types, such as HPV 6 and 11, primarily cause benign lesions like genital warts. In contrast, high-risk types, including HPV 16, 18, and 31, are strongly associated with precancerous lesions and various malignancies, including cervical, anal, and oropharyngeal cancers 9.

Despite the widespread prevalence of HPV infections, most individuals with high-risk HPV do not develop cancer. However, persistent infection, combined with genetic susceptibility and other environmental factors, increases the risk of malignant transformation. Vaccination against high-risk HPV strains has been shown to significantly reduce the incidence of HPV-associated cancers, making prevention an effective strategy in combating this viral-induced oncogenesis.

This manuscript explores the complex relationship between HPV and cancer, with a particular focus on the molecular mechanisms of oncogenesis driven by HPV infection. We will examine the role of E6 and E7 oncoproteins in tumor progression, the epidemiology of HPV-related cancers, and emerging strategies for diagnosis, prevention, and treatment.

Overview of Human papillomavirus virus

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a widespread virus known for its ability to infect epithelial cells of the skin and mucosa, leading to both benign and malignant lesions. It is primarily transmitted through direct skin-to-skin contact, including sexual contact, making it one of the most common sexually transmitted infections worldwide.

We begin with an exploration of HPV virology. HPV is a member of the Papillomaviridae family, one of the oldest known viral families 10. It can infect epithelial cells of the skin, as well as the oral and genital mucosa 11. The viral particles, or virions, exhibit a consistent icosahedral structure 11, with a diameter ranging from 50 to 55 nm 12, 13 and a molecular weight of 5 × 10⁶ Da. HPV contains circular double-stranded DNA of approximately 8000 base pairs, which is associated with histone-like proteins 14.

Next, we delve into the mechanisms of carcinogenesis. The HPV genome is organized into three distinct regions: (1) the early (E) region, which includes the E1, E2, E4, E5, E6, and E7 genes involved in viral replication; (2) the late (L) region, responsible for encoding the primary (L1) and secondary (L2) capsid proteins; and (3) a non-coding region (NCR), also referred to as the long control region (LCR), positioned between the L1 and E6 open reading frames (ORFs) (Figure 1). Although it does not code for proteins, the LCR contains key regulatory elements essential for viral DNA replication and transcription, including the origin of replication (ori) 15.

Following this, we review the epidemiology of HPV-related cancers. Approximately 280 types of papillomaviruses have been identified in vertebrates 16. While all HPVs have the potential to cause benign proliferative lesions 17, they are classified into low-risk (LR) and high-risk (HR) types based on their association with malignancy. Low-risk types, such as HPV-6 and HPV-11, are primarily responsible for benign warts, while twelve high-risk types (HPV-16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, and 59) are strongly linked to malignant neoplasms. Due to this association, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has classified these HPV types as high-risk (HR) 13.

Among the various HPV types, HR-HPVs 16, 18, 31, 33, and 45, along with LR-HPVs 6 and 11, are the most prevalent strains 18, 19, 20, 21. Although the distribution of these HPV types varies by geographical region 18, HR-HPVs 16, 18, 31, 33, and 45 account for 75% of all HPV-related squamous cell carcinomas and 94% of all adenocarcinomas 18, 21.

Finally, we cover the diagnostic, preventive, and therapeutic strategies for HPV-related cancers. This includes current HPV screening methods, particularly for cervical cancer, the global impact of HPV vaccination programs, and the evolving treatment landscape for HPV-induced cancers. The section concludes with a discussion of the ongoing challenges in the fight against these cancers, as well as potential future directions for research and clinical applications.

HPV and carcinogenesis

For HPV to penetrate and initiate an infectious process, there must be continuity in the epithelial tissues so that the virus can come into contact with the permissive basal cells. Once the virus infects these target cells, viral replication begins in the spinous layer. The assembly of virions occurs in the upper strata of the epithelium, specifically in the differentiated granular cells, as this maturity event is essential for successful viral assembly. Finally, in the squamous cells, virions are expelled and may initiate a new infection cycle 22.

As mentioned earlier, the HPV viral genome is divided into three main regions: the early (E) region, the late (L) region, and the non-coding region (NCR), also known as the long control region (LCR). The early region encodes proteins involved in viral replication (E1, E2) and transformation (E6, E7), while the late region encodes the major capsid proteins L1 and L2 that form the viral structure. The non-coding region contains regulatory elements essential for viral DNA replication and transcription. HPV types are categorized into low-risk (LR) and high-risk (HR) groups based on their association with benign or malignant lesions. High-risk HPV types, such as HPV-16 and HPV-18, are closely linked to cancer development, particularly cervical cancer, due to their ability to disrupt normal cell cycle control through the activity of E6 and E7 oncoproteins, which target tumor suppressor proteins like p53 and retinoblastoma protein (pRB) 22.

The process of high-risk HPV infection initiates when the virus infiltrates host cells via micro-trauma to the genital epithelium during sexual intercourse. This facilitates the active proliferation of diverse HPV types, enabling the viral capsid protein L1 to attach to receptors on basal cells, leading to internalization of the virus through endocytosis, with HPV types 16 and 18 employing Clathrin-mediated endocytosis, while HPV 31 utilizes Caveolin-mediated endocytosis 23, 24, 25. At this point, it is confirmed that the viral DNA is widely disseminated across basal proliferating cells while preserving a minimal quantity of copies to evade immune detection 26. The proliferating basal cells enters the productive phase, amplifying the expression of early viral genes through the non-encoding region (NER), which allows DNA to produce hundreds of copies per cell. As long as the proteins in the viral capsid (L1 and L2) have been synthesized, the inhibition of oncoproteins E6 and E7, which are crucial to this stage of viral genome amplification, results in damage to the cytoskeleton, mitochondrial energy disorder, and the degradation of the tumor suppressor p53, which prevents apoptosis and promotes cell proliferation. This creates new infectious virions with the viral DNA. In the meantime, E7 releases the E2F transcription factor to promote cell cycle advancement by binding to and deactivating the retinoblastoma protein (pRB). E6 and E7 work together to suppress cell cycle regulation, encourage mutations, and make it easier for the viral genome to integrate into the DNA of the host cell. This can result in unchecked cell division and the possible emergence of cancer 27, 28, 29.

This mechanism clearly shows that HPV-induced carcinogenesis begins with the expression of E6 and E7 oncoproteins that block p53 and RB and that immortalize the compromised cell, and thereby, the functionality of their DNA, also, certain experiments have shown that the baseline E6 and E7 expression in HPVs is very low since the E2 protein, through the URR regulatory region remains virtually silenced. Given this, it is evident that only a virus infection with high viral concentrations could generate enough E6 units and E7 to initiate this mechanism. In fact, there is a greater chance of neoplastic transformation in infections with a high viral load, where the immune system is unable to eradicate the infection. We may know the mechanism of immortalization with such a low viral load, though, because it has been shown that some persistent infections with low viral loads produce an effective tumor phenotype. This question was addressed by the finding that the viral DNA was broken up and incorporated into the cellular genome in the majority of carcinomas. Most of the time, some virus pieces in the E2 area losing its ability to act on URR and give the command to maintain the expression of E6 and E7 repressed, thus, a small amount of virus will be deregulated and produce copious amounts of E6 and E7 protein, which begins the process of blocking of p53 and RB so effectively 30.

Cancer types by HPV

Transmission of HPV virus occur by direct contact between the skin and mucous membranes, with sexual relationships is the main form of contact, although there are others such as those which occur between mother and child at the time of childbirth. Rubbing and moisture promote transmission. It appears that transmission through objects such as surgical materials, clothing, and fomites in general occurs. However, the entire virus not just DNA fragments must be spread for infection to occur.

Cervical Cancer (CC)

The first cancer linked to HPV was CC. With about 604,000 new cases in 2020, it ranks fourth among the most common cancers in women. 90% of CC deaths in 2020 happened in low- and middle-income countries. HIV-positive women are more likely to acquire CC, accounting for about 5% of all cases. 31. Persistent infection with high-risk HPV strains is the biggest risk factor for CC 32. Slow-risk HPV types, such as 6, 11, 40–44, 54, 61, 70, 72, 81, and 89, are linked to benign lesions or no disease 33, whereas high-risk variants, such as 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68, are linked to an elevated chance of developing CC 34. There is still uncertainty regarding the oncogenicity of HPV types with a "undetermined risk," such as 3, 7, 10, 27–30, 32, 34, 55, 57, 62, 67, 69, 71, 74, 77, 83,84,85,86,87, 90, 91 35. According to high-risk HPV DNA sequencing, HPV types 16 and 18, which are found in about 70% of invasive carcinomas, are present in 99.8% of CCs 36. Sexually active women over 25 are frequently infected with HPV 37. According to a Taiwanese study, women in the 30- to 44-years old age range had a significantly increased risk, with an estimated 11-fold increase, a 35-fold increase for those in the 45- to 54-year-old age range, and a 49-fold increase for those over 50. Cancer risk may be raised by HPV's ability to integrate into infected cells and cause the synthesis of oncogenic proteins (E6, E7) 38.

Skin cancer

It was found in 2020 by GLOBOCAN that there were 324,635 yearly instances of melanoma skin cancer 39. The link between HPV and skin cancer was initially appeared in people with the uncommon genetic disorder epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV).

Esophageal cancer

In accounting for 70% cases of esophageal cancer, it was found that this cancer predominantly affects men. It classifies as the sixth leading cause of cancer-related death globally, with approximately 604,000 new cases and 544,000 deaths reported each year. This cancer is primarily divided into two subtypes: esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). ESCC represents over 85% of all cases and is most prevalent in regions such as East and South-Central Asia, Eastern and Southern Africa, and Northern Europe. In contrast, EAC is more common in Western countries and its incidence has been rising steadily. Studies show that HPV infection is present in 20% of males and 18.4% of females with ESCC. The most frequently identified HPV genotypes in ESCC include HPV16 (11.4%), followed by HPV18 (2.9%), HPV6 (2.1%), HPV11 (2.0%), HPV52 (1.1%), HPV33 (0.8%), and HPV31 (0.6%) 40.

Lung cancer (LC)

With 2,206,771 occurrences in both males and females combined, LC was the second most common type of cancer in 2020. Although tobacco use is the main risk factor for 80–90% of LC cases, there are other possible causes as well. It ranks as the seventh leading cause of cancer-related death and the eleventh most common kind of cancer. LC can also happen to those who don't smoke. According to research, HPV infection may be a major risk factor for LC in nonsmokers and ought to be taken into account while assessing patients 41.

Breast cancer

The cervix, anogenital region, head and neck, and skin are among the body areas where HPV has a known association with a number of cancers. However, HPV's direct involvement in malignancies like glioblastoma, colorectal, lung, and breast cancers is still debatable, even though it might contribute to early changes throughout time. Plasmids harboring HPV 16 and 18 immortalized mammary epithelial cells, as demonstrated by Band et al. 42. This finding raised the possibility that oncogenic HPV types could contribute to the development of breast cancer.

Anal cancer

Vulvar cancer

After ovarian, uterine, and CC cancers, vulvar cancer is the fourth most frequent type of gynecological cancer, accounting for 3–5% of all gynecological malignancies. Every year, about 27,000 women worldwide receive a vulvar cancer diagnosis. Asia has recorded the lowest incidence of vulvar cancer, whereas Europe, North and South America, and Oceania had the highest rates 45.

Diagnostics, prevention and therapy

Vaccines

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) currently approved three preventive HPV vaccines; (i) Gardasil (tetravalent vaccine that works against HPVs 18, 16, 11 and 6), (ii) Cervarix (bivalent vaccine that works against high risk HPVs 18 and 16) and (iii) Gardasil-9 (nonavalent vaccine that works against HPVs 58, 52, 45, 33, 31, 18, 16, 11 and 6). Also, there are currently three other HPV vaccinations on the market: Cervavac, Walwax, and Cecolin 46, 47. Both girls and boys between the ages of 9 and 14 can receive the Cervavac vaccine in a single dose or in two doses spaced six months apart.

Walvax and Cecolin, on the other hand, are prescribed in two doses to girls aged 9 to 14. Over 90% of main high-risk HPVs are protected against by these vaccines. These vaccines have been created with recombinant DNA technology, in which vaccines employ virus-like particles, or VLPs, which have been demonstrated to be extremely immunogenic, completely safe, and have been shown to produce high antibody titers and herd immunity when given to teenage girls between the ages of 9 and 19 46. However, due to their lack of therapeutic efficacy, these vaccinations are unable to eradicate pre-existing HPV infections. So that to achieve highest efficiency of these vaccine against this viral infection, women must be vaccinated prior to engaging in sexual activity or having an HPV infection 47.

CRISPR-Cas9 for HPV therapeutics

CRISPR/Cas9 is a novel genetic research technique that has replaced zinc-finger nucleases (ZFN) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALEN). For every new target site, ZNFs and TALENs require recoding of proteins using large DNA segments (500–1,500 bp). In contrast, CRISPER-Cas9 can be easily modified to target any genomic sequence by changing the 20 bp protospacer of the guide RNA 48.

HPV causes tumor spread and transforming normal cells into malignant ones by using its oncoproteins to boost viral load and maintain viral replication. Additionally, the E6 and E7 oncoproteins inactivate the p53 and pRB genes, which are essential for carcinogenesis, and deactivate the apoptotic pathway. This happen by initiation of unwinds HPV's supercoiled circular DNA by the E1 and E2 complex 49. CRISPR/Cas9 uses single guide RNAs to create specific DNA double-strand breaks and remove a specific gene of interest. This function was performed by the Cas9 nuclease and DNA break was repaired by joining the non-homologous ends 55.

Before receiving therapy, both animal and human studies have been conducted to determine the benefits and drawbacks of utilizing viral delivery mechanisms, such as adenoviruses and lentiviruses, compared with non-viral delivery mechanisms, including electroporation, microinjection and lipid-based nano particles, for this therapy. It has been found that the CRISPR-Cas9 technique can effectively modify the E7 and E6 genes, resulting in reactivation of the pRB and p53 genes, respectively 51. By generating a site-specific guide RNA for the protospacer-adjacent motif sequence of both genes, the genome guardian is relaxed, allowing the Cas9 protein to cut the desired gene region of the viral DNA 52. Also, stopping viral DNA replication in its tracks may also be helpful especially in early stages 53. In a study, Cancer Cervical cells (CC) were introduced into naked mice and they were treated with the CRISPR/Cas9 system. This stopped the tumors from growing and caused more tumor cells to die by targeting E6 and E7. Gao and his colleagues did another study that showed that using CRISPR/Cas9 to target HPV16 E7 could effectively downregulate E7 protein both in vivo and in vitro. This means that it could be used as a therapeutic option for HPV-related cervical cancer and precancerous tumors 54, 55. Additionally, CRISPR/Cas9 combo treatments have demonstrated encouraging results in CC treatment. For instance, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated HPV deletion and immune checkpoint inhibitor PD1 have demonstrated a synergistic anticancer impact on CC 56. When CC was treated with a combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors, antiprogrammed death-1 antibodies, and HPV-targeting guide RNA–liposomes, Zhen and colleagues saw very strong antitumor effects. In the CC model, combinatorial treatment also produced immunological memory 57.

RNA-based therapeutics for HPV

Short/small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) are double-stranded RNAs with two base pair 3' overhangs and a length of almost 21 nucleotides. Through the mRNA degradation of particular target genes in the cytoplasm, they reduce gene expression 58. As a result, the gene target protein's highly effective and targeted synthesis is lost. Three siRNA formulations have been approved for clinical usage by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA): Oxlumo (lumasiran) for primary hyperoxaluria type1, Givosiran (Givlaari) for acute hepatic porphyria, and Patisiran (Onpattro) for hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis 59.

Conclusion

Human papillomavirus (HPV) stands as a pivotal contributor to the global cancer burden, particularly in anogenital and oropharyngeal malignancies. Its oncogenic potential is primarily mediated through the persistent expression of viral oncoproteins E6 and E7, which disrupt key tumor suppressor pathways, notably p53 and Rb. The advent of prophylactic HPV vaccines has dramatically altered the landscape of HPV-associated disease prevention, offering a powerful tool to curb the incidence of cervical and other HPV-related cancers. Moreover, emerging technologies such as CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing hold promise for therapeutic intervention by directly targeting integrated HPV DNA. Despite these advances, challenges remain in ensuring widespread vaccine uptake, developing effective screening programs, and translating gene-editing techniques into clinical practice. Continued interdisciplinary research and public health efforts are essential to eliminate the burden of HPV-associated cancers and to pave the way for precision prevention and treatment strategies.

Author Contributions

Equal contributions in writing -reviewing and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research received no external funding

Abbreviations

References

- 1.Hu M, Wang B, Li J, Wu C. (2024) Editorial: The association between viral infection and human cancers. Front Microbiol. 10-3389.

- 2.Plummer M, C de Martel, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Bray F et al. (2016) Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2012: a synthetic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 4, 609-16.

- 3.Rous P. (1910) A transmissible avian neoplasm (sarcoma of the common fowl). , J Exp Med 12, 10-1016.

- 4.Rous P. (1911) A sarcoma of the fowl transmissible by an agent separable from the tumor cells. J Exp Med. 13-397.

- 6.Epstein M A, Achong B G, Barr Y M.Virus particles in cultured lymphoblasts from Burkitt’s lymphoma. , Lancet 1964, 702-3.

- 7.Moore P S, Chang Y. (2010) Why do viruses cause cancer? Highlights of the first century of human tumour virology. Nat Rev Cancer. 10, 878-89.

- 8.Parkin D M. (2002) The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year. , Int J Cancer 118-3030.

- 9.Muñoz N, Bosch F X, S de. (2003) Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. , N Engl J Med 348-518.

- 11.Araldi R P, Sant’Ana T A, Módolo D G, de Melo TC, Spadacci-Morena D D et al. (2018) The human papillomavirus (HPV)-related cancer biology: An overview. Biomed Pharmacother. 106-1537.

- 12.Larsen P M, Storgaard L, Fey S J. (1987) Proteins present in bovine papillomavirus particles. , J 61-11.

- 13.Boccardo E, Lepique A P, Villa L L. (2010) The role of inflammation in HPV carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 31(11), 10-1093.

- 14.Das Graças M, Leto P, Francisco G, Júnior S, Porro A M et al. (2011) Human papillomavirus infection: etiopathogenesis, molecular biology and clinical manifestations. An Bras Dermatol. 86-2.

- 15.Tommasino M. (2014) The human papillomavirus family and its role in carcinogenesis. , Semin Cancer Biol 26-13.

- 16.Araldi R P, SMR Assaf, de Carvalho RF, de Carvalho MACR, de Souza JM et al. (2017) Papillomaviruses: A systematic review. Genet Mol Biol. 40(1), 1-21.

- 17.Reshkin S J, Bellizzi A, Caldeira S, Albarani V, Malanchi I et al. (2000) Na+/H+ exchanger-dependent intracellular alkalinization is an early event in malignant transformation. , FASEB J 14(14), 10-1096.

- 18.Flaherty A, Kim T, Giuliano A, Magliocco A, Hakky T S et al. (2014) Implications for human papillomavirus in penile cancer. Urol Oncol. 32(1), 10-1016.

- 19.R De Vincenzo, Ricci C, Conte C, Scambia G.HPV vaccine cross-protection: Highlights on additional clinical benefit. , Gynecol Oncol 130(3), 642-51.

- 20.Serrano B, S De, Tous S, Quiros B, Muñoz N et al. (2015) Human papillomavirus genotype attribution in female anogenital lesions. , Eur J Cancer 51-13.

- 21.Clifford G M, Gallus S, Herrero R, Muñoz N, PJF Snijders et al. (2005) Worldwide distribution of HPV types in cytologically normal women. Lancet. 366(9490), 10-1016.

- 22.Hoffmann R, Hirt B, Bechtold V, Beard P, Raj K. (2006) Different modes of HPV DNA replication during maintenance. , J Virol 80, 10-1128.

- 23.Bousarghin L, Touze A, Sizaret P Y, Coursaget P. (2003) HPV types 16, 31, and 58 use different endocytosis pathways. , J Virol 77, 10-1128.

- 24.Day P M, Lowy D R, Schiller J T. (2003) Papillomaviruses infect cells via clathrin-dependent pathway. Virology. 307-1.

- 25.Smith J L, Campos S K, Ozbun M A. (2007) HPV31 uses caveolin 1- and dynamin 2-mediated entry. , J Virol 81, 10-1128.

- 26.Ling Peh W, Middleton K, Christensen N. (2002) Life cycle heterogeneity in animal models of HPV-associated disease. , J Virol 76, 0-1128.

- 27.Nakahara T, Nishimura A, Tanaka M. (2002) Modulation of the cell cycle by HPV18 E4. J Virol. 76, 10-1128.

- 28.Zur Hausen H. (2000) Papillomaviruses causing cancer: evasion from host-cell control. , J Natl Cancer Inst 92, 690-8.

- 29.Lu Z, Hu X, Li Y. (2004) HPV16 E6 interferes with insulin signaling via tuberin. J Biol Chem. 279-35664.

- 30.Alba A, Cararach M, Rodríguez-Cerdeira C. (2009) HPV in pathology: description, pathogenesis, epidemiology. , Open Dermatol J 3-10.

- 31.Stelzle D, Tanaka L F, Lee K K. (2021) Global burden of cervical cancer associated with HIV. Lancet Glob Health. 9(2), 161-71.

- 32.Olusola P, Banerjee H N, Philley J V, Dasgupta S. (2019) HPV-associated cervical cancer and health disparities. Cells. 8(6), 622-10.

- 33.Salambanga C, Zohoncon T M, IMA Traoré. (2019) Forte prévalence du HPV à Ouagadougou. Med Sante Trop. 29(3), 302-5.

- 34.Nielsen A, Iftner T, Nørgaard M.. Low-risk HPV and abnormal cervical cytology in 40,000 Danish women. Sex Transm Infect 2012 88(8), 627-32.

- 36.S de, Brotons M, Pavon M A. (2018) Natural history of HPV infection. , Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 47, 2-13.

- 38.Mbuya W, Held K, Mcharo R D.. Depletion of HPV-specific T-cells in HIV+ women. Front Immunol 2021,12 4473-10.

- 39.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel R L.Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN. , CA Cancer J Clin 71(3), 209-49.

- 40.Xu H, Lin A, Chen Y. (2017) . Prevalence of cervical HPV genotypes in Taizhou. BMJ Open 7(6), 014135-10.

- 41.Schabath M B, Cote M L. (2019) Cancer progress and priorities: lung cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 28(10), 1563-79.

- 42.Sigaroodi A, Nadji S A, Naghshvar F. (2012) HPV association with breast cancer in Iran. Sci World J. 1-6.

- 43.Parkin D M. (2002) Global health burden of infection-associated cancers in. , Int 118(12), 3030-44.

- 44.Morris V K, Rashid A, Rodriguez-Bigas M. (2015) . HPV/p16 in metastatic anal cancer. Oncologist 1247-52.

- 46.Das B C, Hussain S, Nasare V, Bharadwaj M. (2008) HPV vaccines in India: prospects and prejudices. Vaccine. 26(22), 2669-76.

- 47.Gupta S, Kumar P, Das B C.Cervical cancer-free India: challenges and opportunities. , Indian J Med Res 158(56), 470-5.

- 48.Gupta R M, Musunuru K. (2014) Expanding gene editing tools: ZFNs, TALENs. , CRISPR. J Clin Invest 124(10), 4154-61.

- 49.Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Kyriazoglou A, Liontos M. (2020) . Trends in HPV prevention 25(3), 1281-5.

- 50.Inturiet R, Jemth P. (2021) . CRISPR/Cas9 inactivation of HPV oncogenes induces senescence. Virology 562-92.

- 51.Jubair L, Fallaha S, McMillan N A. (2019) Systemic CRISPR/Cas9 delivery eliminates tumors. Mol Ther. 27(12), 2091-9.

- 52.Yoshiba T, Saga Y, Urabe M.. CRISPR/Cas9 targeting HPV E6 for cervical cancer. Oncol Lett 2019 17(2), 2197-202.

- 53.Ling K, Yang L, Yang N. (2020) . Nonviral CRISPR/Cas9 targeting of HPV18 E6/E7. Hum Gene Ther 31(5), 297-308.

- 56.Zhen S, Lu J, Liu Y H. (2020) Synergistic antitumor effect:. PD-1 blockade + CRISPR-Cas9. Cancer Gene Ther 27(3), 168-78.

- 57.Zhen S, Chen H, Lu J.. Intravaginal CRISPR–Cas9 for HPV infection. J Med Virol. 2023, 95(2) 28552-10.